This article is about irrigation in agriculture. For other uses, see Irrigation (disambiguation).

An irrigation sprinkler watering a lawn

Irrigation canal in Osmaniye, Turkey

Irrigation is the method in which a controlled amount of water is supplied to plants at regular intervals for agriculture. It is used to assist in the growing of agricultural crops, maintenance of landscapes, and revegetation of disturbed soils in dry areas and during periods of inadequate rainfall. Additionally, irrigation also has a few other uses in crop production, which include protecting plants against frost,[1] suppressing weed growth in grain fields[2] and preventing soil consolidation.[3] In contrast, agriculture that relies only on direct rainfall is referred to as rain-fed or dry land farming.

Irrigation systems are also used for dust suppression, disposal of sewage, and in mining. Irrigation is often studied together with drainage, which is the natural or artificial removal of surface a nd sub-surface water from a given area.

Irrigation has been a central feature of agriculture for over 5,000 years and is the product of many cultures. Historically, it was the basis for economies and societies across the globe, from Asia to the Southwestern United States.

Contents

1 History

1.1 China

1.2 Korea

1.3 North America

2 Present extent

3 Types of irrigation

3.1 Surface irrigation

3.2 Localized irrigation

3.2.1 Subsurface textile irrigation

3.2.2 Drip irrigation

3.3 Irrigation using sprinkler Sprinkler System Installation systems

3.3.1 Irrigation using Center pivot

3.3.2 Irrigation by Lateral move (side roll, wheel line, wheelmove)[32][33]

3.4 Sub-irrigation

3.5 Irrigation Automatically, non-electric using buckets and ropes

3.6 Irrigation using water condensed from humid air

3.7 In-groun d irrigation

4 Water sources

5 Efficiency

6 Technical challenges

7 See also

8 References

9 Further reading

9.1 Journals

10 External links

History

Animal-powered irrigation, Upper Egypt, ca. 1846

Inside a karez tunnel at Turpan, Sinkiang

irrigation in Tamil Nadu, India

Crop sprinklers near Rio Vista, California

Residential flood irrigation in Phoenix, Arizona in the United States of America.

Archaeological investigation has found evidence of irrigation where the natural rainfall was insufficient to support crops for rainfed agriculture.

Perennial irrigation was practiced in the Mesopotamian plain whereby crops were regularly watered throughout the growing season by coaxing water through a matrix of small channels formed in the field.[4]Ancient Egyptians practiced Basin irrigation using the flooding of the Nile to inundate land plots which had been surrounded by dykes. The flood water was held until the fertile sediment had settled before the surplus was returned to the watercourse.[5] There is evidence of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Amenemhet III in the twelfth dynasty (about 1800 BCE) using the natural lake of the Faiyum Oasis as a reservoir to store surpluses of water for use during the dry seasons, the lake swelled annually from flooding of the Nile.[6]

The Ancient Nubians developed a form of irrigation by using a waterwheel-like device called a sakia. Irrigation began in Nubia some time between the third and second millennium BCE.[7] It largely depended upon the flood waters that would flow through the Nile River and other rivers in what is now the Sudan.[8]

In sub-Saharan Africa irrigation reached the Niger River region cultures and civilizations by the first or second millennium BCE and was based on wet season flooding and water harvesting.[9][10]

Terrace irrigation is evidenced in pre-Columbian America, early Syria, India, and China.[5] In t he Zana Valley of the Andes Mountains in Peru, archaeologists found remains of three irrigation canals radiocarbon dated from the 4th millennium BCE, the 3rd millennium BCE and the 9th century CE. These canals are the earliest record of irrigation in the New World. Traces of a canal possibly dating from the 5th millennium BCE were found under the 4th millennium canal.[11] Sophisticated irrigation and storage systems were developed by the Indus Valley Civilization in present-day Pakistan and North India, including the reservoirs at Girnar in 3000 BCE and an early canal irrigation system from circa 2600 BCE.[12][13] Large scale agriculture was practiced and an extensive network of canals was used for the purpose of irrigation.

Ancient Persia (modern day Iran) as far back as the 6th millennium BCE, where barley was grown in areas where the natural rainfall was insufficient to support such a crop.[14] The Qanats, developed in ancient Persia in about 800 BCE, are among the oldest known irrigation methods still in use today. They are now found in Asia, the Middle East and North Africa. The system comprises a network of vertical wells and gently sloping tunnels driven into the sides of cliffs and steep hills to tap groundwater.[15] The noria, a water wheel with clay pots around the rim powered by the flow of the stream (or by animals where the water source was still), was first brought into use at about this time, by Roman settlers in North Africa. By 150 BCE the pots were fitted with valves to allow smoother filling as they were forced into the water.[16]

The irrigation works of ancient Sri Lanka, the earliest dating from about 300 BCE, in the reign of King Pandukabhaya and under continuous development for the next thousand years, were one of the most complex irrigation systems of the ancient world. In addition to underground canals, the Sinhalese were the first to build completely artificial reservoirs to store water. Due to their engineering superior ity in this sector, they were often called 'masters of irrigation'. Most of these irrigation systems still exist undamaged up to now, in Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa, because of the advanced and precise engineering. The system was extensively restored and further extended during the reign of King Parakrama Bahu (1153-1186 CE).[17]

China

The oldest known hydraulic engineers of China were Sunshu Ao (6th century BCE) of the Spring and Autumn period and Ximen Bao (5th century BCE) of the Warring States period, both of whom worked on large irrigation projects. In the Sichuan region belonging to the State of Qin of ancient China, the Dujiangyan Irrigation System was built in 256 BCE to irrigate an enormous area of farmland that today still supplies water.[18] By the 2nd century AD, during the Han Dynasty, the Chinese also used chain pumps that lifted water from lower elevation to higher elevation.[19] These were powered by manual foot pedal, hydraulic waterwheels, or rotatin g mechanical wheels pulled by oxen.[20] The water was used for public works of providing water for urban residential quarters and palace gardens, but mostly for irrigation of farmland canals and channels in the fields.[21]

Korea

In 15th century Korea, the world's first rain gauge, uryanggye (Korean:???), was invented in 1441. The inventor was Jang Yeong-sil, a Korean engineer of the Joseon Dynasty, under the active direction of the king, Sejong the Great. It was installed in irrigation tanks as part of a nationwide system to measure and collect rainfall for agricultural applications. With this instrument, planners and farmers could make better use of the information gathered in the survey.[22]

North America

Main article: Hohokam

The earliest agricultural irrigation canal system known in the U.S. dates to between 1200 B.C. and 800 B.C. and was discovered in Marana, Arizona (adjacent to Tucson) in 2009.[23] The irrigation canal system predates the Ho hokam culture by two thousand years and belongs to an unidentified culture. In North America, the Hohokam were the only culture known to rely on irrigation canals to water their crops, and their irrigation systems supported the largest population in the Southwest by AD 1300. The Hohokam constructed an assortment of simple canals combined with weirs in their various agricultural pursuits. Between the 7th and 14th centuries, they also built and maintained extensive irrigation networks along the lower Salt and middle Gila rivers that rivaled the complexity of those used in the ancient Near East, Egypt, and China. These were constructed using relatively simple excavation tools, without the benefit of advanced engineering technologies, and achieved drops of a few feet per mile, balancing erosion and siltation. The Hohokam cultivated varieties of cotton, tobacco, maize, beans and squash, as well as harvested an assortment of wild plants. Late in the Hohokam Chronological Sequence, they al so used extensive dry-farming systems, primarily to grow agave for food and fiber. Their reliance on agricultural strategies based on canal irrigation, vital in their less than hospitable desert environment and arid climate, provided the basis for the aggregation of rural populations into stable urban centers.[24]

Present extent

Irriga tion ditch in Montour County, Pennsylvania, off Strawberry Ridge Road

In the mid-20th century, the advent of diesel and electric motors led to systems that could pump groundwater out of major aquifers faster than drainage basins could refill them. This can lead to permanent loss of aquifer capacity, decreased water quality, ground subsidence, and other problems. The future of food production in such areas as the North China Plain, the Punjab, and the Great Plains of the US is threatened by this phenomenon.[25][26]

At the global scale, 2,788,000km (689 million acres) of fertile land was equipped with irrigation infrastructure around the year 2000. About 68% of the area equipped for irrigation is located in Asia, 17% in the Americas, 9% in Europe, 5% in Africa and 1% in Oceania. The largest contiguous areas of high irrigation density are found:

In Northern India and Pakistan along the Ganges and Indus rivers

In the Hai He, Huang He and Yangtze basins in Chi na

Along the Nile river in Egypt and Sudan

In the Mississippi-Missouri river basin and in parts of California

Smaller irrigation areas are spread across almost all populated parts of the world.[27]

Only eight years later in 2008, the scale of irrigated land increased to an estimated total of 3,245,566km (802 million Sprinkler System Installation acres), which is nearly the size of India.[28]

Types of irrigation

Basin flood irrigation of wheat

Irrigation of land in Punjab, Pakistan

Various types of irrigation techn iques differ in how the water obtained from the source is distributed within the field. In general, the goal is to supply the entire field uniformly with water, so that each plant has the amount of water it needs, neither too much nor too little.

Surface irrigation

Main article: Surface irrigation

In surface (furrow, flood, or level basin) irrigation systems, water moves across the surface of agricultural lands, in order to wet it and infiltrate into the soil. Surface irrigation can be subdivided into furrow, borderstrip or basin irrigation. It is often called flood irrigation when the irrigation results in flooding or near flooding of the cultivated land. Historically, this has been the most common method of irrigating agricultural land and still used in most parts of the world.

Where water levels from the irrigation source permit, the levels are controlled by dikes, usually plugged by soil. This is often seen in terraced rice fields (rice paddies), wher e the method is used to flood or control the level of water in each distinct field. In some cases, the water is pumped, or lifted by human or animal power to the level of the land. The field water efficiency of surface irrigation is typically lower than other forms of irrigation but has the potential for efficiencies in the range of 70% - 90% under appropriate management.

Localized irrigation

Impact sprinkler he ad

Localized irrigation is a system where water is distributed under low pressure through a piped network, in a pre-determined pattern, and applied as a small discharge to each plant or adjacent to it. Drip irrigation, spray or micro-sprinkler irrigation and bubbler irrigation belong to this category of irrigation methods.[29]

Subsurface textile irrigation

Diagram showing the structure of an example SSTI installation

Main article: Subsurface textile irrigation

Subsurface Textile Irrigation (SSTI) is a tec hnology designed specifically for subsurface irrigation in all soil textures from desert sands to heavy clays. A typical subsurface textile irrigation system has an impermeable base layer (usually polyethylene or polypropylene), a drip line running along that base, a layer of geotextile on top of the drip line and, finally, a narrow impermeable layer on top of the geotextile (see diagram). Unlike standard drip irrigation, the spacing of emitters in the drip pipe is not critical as the geotextile moves the water along the fabric up to 2m from the dripper.

Drip irrigation

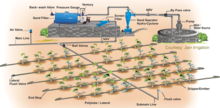

Drip irrigation layout and its parts

Drip irrigation - a dripper in action

Grapes in Petrolina, only made possible in this semi arid area by drip irrigation

Main article: Drip irrigation

Drip (or micro) irrigation, also known as trickle irrigation, functions as its name suggests. In this system water falls drop by drop just at the position of roots. Water is delivered at or near the root zone of plants, drop by drop. This method can be the most water-efficient method of irrigation,[30] if managed properly, since evaporation and runoff are minimized. The field water efficiency of drip irrigation is typically in the range of 80 to 90 percent when managed correctly.

In modern agriculture, drip irrigation is often combined with plastic mulch, further reducing evaporation, and is also the means of delivery of fertilizer. The process is known as fertigation.

Deep percolation, where water moves below the root zone, can occur if a dri p system is operated for too long or if the delivery rate is too high. Drip irrigation methods range from very high-tech and computerized to low-tech and labor-intensive. Lower water pressures are usually needed than for most other types of systems, with the exception of low energy center pivot systems and surface irrigation systems, and the system can be designed for uniformity throughout a field or for precise water delivery to individual plants in a landscape containing a mix of plant species. Although it is difficult to regulate pressure on steep slopes, pressure compensating emitters are available, so the field does not have to be level. High-tech solutions involve precisely calibrated emitters located along lines of tubing that extend from a computerized set of valves.

Irrigation using sprinkler systems

Sprinkler irrigation of blueberries in Plainville, New York, United States

A traveling sprinkler at Millets Farm Centre, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom

Further information: Irrigation sprinkler

In sprinkler or overhead irrigation, water is piped to one or more central locations within the field and distributed by overhead high-pressure sprinklers or guns. A system utilizing sprinklers, sprays, or guns mounted overhead on permanently installed risers is often referred to as a solid-set irrigation system. Higher pressure sprinklers that rotate are called rotors an are driven by a ball drive, gear drive, or impact mechanism. Rotors can be designed to rotate in a full or partial circle. Guns are similar to rotors, except that they generally operate at very high pressures of 40 to 130lbf/in (275 to 900 kPa) and flows of 50 to 1200 US gal/min (3 to 76 L/s), usually with nozzle diameters in the range of 0.5 to 1.9inches (10 to 50mm). Guns are used not only for irrigation, but also for industrial applications such as dust suppression and logging.

Sprinklers can also be mounted on moving platforms connected to the water source by a hose. Automatically moving wheeled systems known as traveling sprinklers may irrigate areas such as small farms, sports fields, parks, pastures, and cemeteries unattended. Most of these utilize a leng th of polyethylene tubing wound on a steel drum. As the tubing is wound on the drum powered by the irrigation water or a small gas engine, the sprinkler is pulled across the field. When the sprinkler arrives back at the reel the system shuts off. This type of system is known to most people as a "waterreel" traveling irrigation sprinkler and they are used extensively for dust suppression, irrigation, and land application of waste water.

Other travelers use a flat rubber hose that is dragged along behind while the sprinkler platform is pulled by a cable. These cable-type travelers are definitely old technology and their use is limited in today's modern irrigation projects.

Irrigation using Center pivot

A small center pivot system from beginning to end

The hub of a center-pivot irrigation system

Rotator style pivot applicator sprinkler

Center pivot with drop sprinklers

Wheel line irrigation system in Idaho, 2001

Main article: Center pivot irrigation

Center pivot irrigation

Center pivot irrigation is a form of sprinkler irrigation consisting of several segments of pipe (usually galvanized steel or aluminium) joined together and supported by trusses, mounted on wheeled towers w ith sprinklers positioned along its length.[31] The system moves in a circular pattern and is fed with water from the pivot point at the center of the arc. These systems are found and used in all parts of the world and allow irrigation of all types of terrain. Newer systems have drop sprinkler heads as shown in the image that follows.

Most center pivot systems now have drops hanging from a u-shaped pipe attached at the top of the pipe with sprinkler head that are positioned a few feet (at most) above the crop, thus limiting evaporative losses. Drops can also be used with drag hoses or bubblers that deposit the water directly on the ground between crops. Crops are often planted in a circle to conform to the center pivot. This type of system is known as LEPA (Low Energy Precision Application). Originally, most center pivots were water powered. These were replaced by hydraulic systems (T-L Irrigation) and electric motor driven systems (Reinke, Valley, Zimmatic). Many modern pivo ts feature GPS devices.

Irrigation by Lateral move (side roll, wheel line, wheelmove)[32][33]

A series of pipes, each with a wheel of about 1.5 m diameter permanently affixed to its midpoint, and sprinklers along its length, are coupled together. Water is supplied at one end using a large hose. After sufficient irrigation has been applied to one strip of the field, the hose is removed, the water drained from the system, and the assembly rolled either by hand or with a purpose-built mechanism, so that the sprinklers are moved to a different position across the field. The hose is reconnected. The process is repeated in a pattern until the whole field has been irrigated.

This system is less expensive to install than a center pivot, but much more labor-intensive to operate - it does not travel automatically across the field: it applies water in a stationary strip, must be drained, and then rolled to a new strip. Most systems use 4 or 5-inch (130mm) diameter aluminum pipe. The pipe doubles both as water transport and as an axle for rotating all the wheels. A drive system (often found near the centre of the wheel line) rotates the clamped-together pipe sections as a single axle, rolling the whole wheel line. Manual adjustment of individual wheel positions may be necessary if the system becomes misaligned.

Wheel line systems are limited in the amount of water they can carry, and limited in the height of crops that can be irrigated. One useful feature of a lateral move system is that it consists of sections that can be easily disconnected, adapting to field shape as the line is moved. They are most often used for small, rectilinear, or oddly-shaped fields, hilly or mountainous regions, or in regions where labor is inexpensive.

Sub-irrigation

Subirrigation has been used for many years in field crops in areas with high water tables. It is a method of artificially raising the water table to allow the soil to be moistened from bel ow the plants' root zone. Often those systems are located on permanent grasslands in lowlands or river valleys and combined with drainage infrastructure. A system of pumping stations, canals, weirs and gates allows it to increase or decrease the water level in a network of ditches and thereby control the water table.

Sub-irrigation is also used in commercial greenhouse production, usually for potted plants. Water is delivered from below, absorbed upwards, and the excess collected for recycling. Typically, a solution of water and nutrients floods a container or flows through a trough for a short period of time, 10-20 minutes, and is then pumped back into a holding tank for reuse. Sub-irrigation in greenhouses requires fairly sophisticated, expensive equipment and management. Advantages are water and nutrient conservation, and labor-saving through lowered system maintenance and automation. It is similar in principle and action to subsurface basin irrigation.

Irrigation A utomatically, non-electric using buckets and ropes

Besides the common manual watering by bucket, an automated, natural version of this also exists. Using plain polyester ropes combined with a prepared ground mixture can be used to water plants from a vessel filled with water.[34][35][36]

The ground mixture would need to be made depending on the plant itself, yet would mostly consist of black potting soil, vermiculite and perlite. This system would (with certain crops) allow to save expenses as it does not consume any electricity and only little water (unlike sprinklers, water timers, etc.). However, it may only be used with certain crops (probably mostly larger crops that do not need a humid environment; perhaps e.g. paprikas).

Irrigation using water condensed from humid air

In countries where at night, humid air sweeps the countryside.Water can be obtained from the humid air by condensation onto cold surfaces. This is for example practiced in the vineyar ds at Lanzarote using stones to condense water or with various fog collectors based on canvas or foil sheets.

In-ground irrigation

Most commercial and residential irrigation systems are "in ground" systems, which means that everything is buried in the ground. With the pipes, sprinklers, emitters (drippers), and irrigation valves being hidden, it makes for a cleaner, more presentable landscape without garden hoses or other items having to be moved around manually. This does, however, create some drawbacks in the maintenance of a completely buried system.

Most irrigation systems are divided into zones. A zone is a single irrigation valve and one or a group of drippers or sprinklers that are connected by pipes or tubes. Irrigation systems are divided into zones because there is usually not enough pressure and available flow to run sprinklers for an entire yard or sports field at once. Each zone has a solenoid valve on it that is controlled via wire by an irrigation controller. The irrigation controller is either a mechanical (now the "dinosaur" type) or electrical device that signals a zone to turn on at a specific time and keeps it on for a specified amount of time. "Smart Controller" is a recent term for a controller that is capable of adjusting the watering time by itself in response to current environmental conditions. The smart controller determines current conditions by means of historic weather data for the local area, a soil moisture sensor (water potential or water content), rain sensor, or in more sophisticated systems satellite feed weather station, or a combination of these.

When a zone comes on, the water flows through the lateral lines and ultimately ends up at the irrigation emitter (drip) or sprinkler heads. Many sprinklers have pipe thread inlets on the bottom of them which allows a fitting and the pipe to be attached to them. The sprinklers are usually installed with the top of the head flush with the ground surface. When the water is pressurized, the head will pop up out of the ground and water the desired area until the valve closes and shuts off that zone. Once there is no more water pressure in the lateral line, the sprinkler head will retract back into the ground. Emitters are generally laid on the soil surface or buried a few inches to reduce evaporation losses.

Water sources

Irrigation is underway by pump-enabled extraction directly from the Gumti, seen in the background, in Comilla, Bangladesh.

Irrigation water can come from groundwater (extracted from springs or by using wells), from surface water (withdrawn from rivers, lakes or reservoirs) or from non-conventional sources like treated wastewater, desalinated water or drainage water. A special form of irrigation using surface water is spate irrigation, also called floodwater harvesting. In case of a flood (spate), water is diverted to normally dry river beds (wadis) using a network of dams, gates and channels and spread over large areas. The moisture stored in the soil will be used thereafter to grow crops. Spate irrigation areas are in particular located in semi-arid or arid, mountainous regions. While floodwat er harvesting belongs to the accepted irrigation methods, rainwater harvesting is usually not considered as a form of irrigation. Rainwater harvesting is the collection of runoff water from roofs or unused land and the concentration of this.

Around 90% of wastewater produced globally remains untreated, causing widespread water pollution, especially in low-income countries. Increasingly, agriculture uses untreated wastewater as a source of irrigation water. Cities provide lucrative markets for fresh produce, so are attractive to farmers. However, because agriculture has to compete for increasingly scarce water resources with industry and http://azlandscapecreations.com/ municipal users (see Water scarcity below), there is often no alternative for farmers but to use water polluted with urban waste, including sewage, directly to water their crops. Significant health hazards can result from using water loaded with pathogens in this w ay, especially if people eat raw vegetables that have been irrigated with the polluted water. The International Water Management Institute has worked in India, Pakistan, Vietnam, Ghana, Ethiopia, Mexico and other countries on various projects aimed at assessing and reducing risks of wastewater irrigation. They advocate a 'multiple-barrier' approach to wastewater use, where farmers are encouraged to adopt various risk-reducing behaviours. These include ceasing irrigation a few days before harvesting to allow pathogens to die off in the sunlight, applying water carefully so it does not contaminate leaves likely to be eaten raw, cleaning vegetables with disinfectant or allowing fecal sludge used in farming to dry before being used as a human manure.[37] The World Health Organization has developed guidelines for safe water use.

There are numer ous benefits of using recycled water for irrigation, including the low cost (when compared to other sources, particularly in an urban area), consistency of supply (regardless of season, climatic conditions and associated water restrictions), and general consistency of quality. Irrigation of recycled wastewater is also considered as a means for plant fertilization and particularly nutrient supplementation. This approach carries with it a risk of soil and water pollution through excessive wastewater application. Hence, a detailed understanding of soil water conditions is essential for effective utilization of wastewater for irrigation.[38]

Efficiency

Young engineers restoring and developing the old Mughal irrigation system during the reign of the Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah II

Modern irrigation methods are efficient enough to supply the entire field uniformly with water, so that each plant has the amount of water it needs, neither too much nor too little.[39] Water use efficiency in the field can be determined as follows:

Field Water Efficiency (%) = (Water Transpired by Crop Water Applied to Field) x 100

Until 1960s, the common perception was that water was an infinite resource. At that time, there were fewer than half the current number of people on the planet. People were not as wealthy as today, consumed fewer calories and ate less meat, so less water was needed to produce their food. They required a third of the volume of water we presently take from rivers. Today, the competition for water resources is much more intense. This is because there are now more than seven billion people on the planet, their consumption of water-thirsty meat and vegetables is rising, and there is increasing competition for water from industry, urbanisation and biofuel crops. To avoid a global water crisis, farmers will have to strive to increase productivity to meet growing demands for food, while industry and cities find ways to use water more efficiently.[40]

Successful agriculture is dependent upon farmers having sufficient access to water. However, water scarcity is already a critical constraint to farming in many parts of the world. With regards to agriculture, the World Bank targets food production and water management as an increasingly global issue that is fostering a growing deb ate.[41]Physical water scarcity is where there is not enough water to meet all demands, including that needed for ecosystems to function effectively. Arid regions frequently suffer from physical water scarcity. It also occurs where water seems abundant but where resources are over-committed. This can happen where there is overdevelopment of hydraulic infrastructure, usually for irrigation. Symptoms of physical water scarcity include environmental degradation and declining groundwater. Economic scarcity, meanwhile, is caused by a lack of investment in water or insufficient human capacity to satisfy the demand for water. Symptoms of economic water scarcity include a lack of infrastructure, with people often having to fetch water from rivers for domestic and agricultural uses. Some 2.8 billion people currently live in water-scarce areas.[42]

Technical challenges

Main article: Environmental impact of irrigation

Irrigation schemes involve solving numerous engineering and economic problems while minimizing negative environmental impact.[43]

Competition for surface water rights.[44]

Overdrafting (depletion) of underground aquifers.

Ground subsidence (e.g. New Orleans, Louisiana)

Underirrigation or irrigation giving only just enough water for the plant (e.g. in drip line irrigation) gives poor soil salinity control which leads to increased soil salinity with consequent buildup of toxic salts on soil surface in areas with high evaporation. This requires either leaching to remove these salts and a method of drainage to carry the salts away. When using drip lines, the leaching is best done regularly at certain intervals (with only a slight excess of water), so that the salt is flushed back under the plant's roots.[45][46]

Overirrigation because of poor distribution uniformity or management wastes water, chemicals, and may lead to water pollution.[47]

Deep drainage (from over-irrigation) may result in rising w ater tables which in some instances will lead to problems of irrigation salinity requiring watertable control by some form of subsurface land drainage.[48][49]

Irrigation with saline or high-sodium water may damage soil structure owing to the formation of alkaline soil

Clogging of filters: It is mostly algae that clog filters, drip installations and nozzles. UV[50] and ultrasonic[51] method can be used for algae control in irrigation systems.

See also

Deficit irrigation

Environmental impact of irrigation

Farm water

Gezira Scheme

Irrigation district

Irrigation management

Irrigation statistics

Leaf Sensor

Lift irrigation schemes

List of countries by irrigated land area

Nano Ganesh

Paddy field

Qanat

Surface irrigation

Tidal irrigation

References

^ Snyder, R. L.; Melo-Abreu, J. P. (2005). "Frost protection: fundamentals, practice, and economics" (PD F). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISSN1684-8241.

^ Williams, J. F.; S. R. Roberts; J. E. Hill; S. C. Scardaci; G. Tibbits. "Managing Water for 'Weed' Control in Rice". UC Davis, Department of Plant Sciences. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

^ "Aridpoop -05-15". Retrieved 2012-06-19.

^ Hill, Donald: A History of Engineering

^ a b p19 Hill

^ "Amenemhet III". Britannica Concise. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

^ G. Mokhtar (1981-01-01). Ancient civilizations of Africa. Unesco. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa. p.309. ISBN9780435948054. Retrieved 2012-06-19 - via Books.google.com.

^ Richard Bulliet, Pamela Kyle Crossley, Daniel Headrick, Steven Hirsch. Pages 53-56 (2008-06-18). The Earth and Its Peoples, Volume I: A Global History, to 1550. Books.google.com. ISBN0618992383. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

^ "Traditional technologies". Fao.org. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

^ "Africa, Eme rging Civilizations In Sub-Sahara Africa. Various Authors; Edited By: R. A. Guisepi". History-world.org. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

^ Dillehay TD, Eling HH Jr, Rossen J (2005). "Preceramic irrigation canals in the Peruvian Andes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (47): 17241-4. PMC1288011

^ Rodda, J. C. and Ubertini, Lucio (2004). The Basis of Civilization - Water Science? pg 161. International Association of Hydrological Sciences (International Association of Hydrological Sciences Press 2004) .

^ "Ancient India Indus Valley Civilization". Minnesota State University "e-museum". Retrieved 2007-01-10.

^ The History of Technology- Irrigation. Encyclopdia Britannica, 1994 edition.

^ "Qanat Irrigation Systems and Homegardens (Iran)". Globally Important Agriculture Heritage Systems. UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

^ Encyclopdia Britannica, 1911 and 1989 editions

^ de Silva, Sena (1998). "Reservoirs of Sri Lanka and their fisheries". UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

^ China- history. Encyclopdia Britannica,1994 edition.

^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. Pages 344-346.

^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 340-343.

^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 33, 110.

^ Baek Seok-gi ??? (1987). Jang Yeong-sil ???. Woongjin Wiin Jeon-gi ?????? 11. Woongjin P ublishing Co., Ltd.

^ "Earliest Canals in America - Archaeology Magazine Archive".

^ James M. Bayman, "The Hohokam of Southwest North America." Journal of World Prehistory 15.3 (2001): 257-311.

^ "A new report says we're draining our aquifers faster than ever". High Country News. 2013-06-22. Retrieved 2014-02-11.

^ "Management of aquifer recharge and discharge processes and aquifer storage equilibrium" (PDF). Groundwater storage is shown to be declining in all populated continents...

^ Siebert, S.; J. Hoogeveen, P. Dll, J-M. Faurs, S. Feick, and K. Frenken (2006-11-10). "The Digital Global Map of Irrigation Areas- Development and Validation of Map Version 4" (PDF). Tropentag 2006- Conference on International Agricultural Research for Development. Bonn, Germany. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

^ The CIA World Factbook, retrieved 2011-10-30

^ Frenken, K. (2005). Irrigation in Africa in figures- AQUASTAT Survey- 2005 (PDF). Food and Agriculture Or ganization of the United Nations. ISBN92-5-105414-2. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

^ Provenzano, Giuseppe (2007). "Using HYDRUS-2D Simulation Model to Evaluate Wetted Soil Volume in Subsurface Drip Irrigation Systems". J. Irrig. Drain Eng. 133 (4): 342-350. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9437(2007)133:4(342).

^ Mader, Shelli (May 25, 2010). "Center pivot irrigation revolutionizes agriculture". The Fence Post Magazine. Retrieved June 6, 2012.

^ Peters, Troy. "Managing Wheel - Lines and Hand - Lines for High Profitability" (PDF). Retrieved 29 May 2015.

^ Hill, Robert. "Wheelmove Sprinkler Irrigation Operation and Management" (PDF). Retrieved 29 May 2015.

^ "Polyester ropes natural irrigation technique". Entheogen.com. Archived from the original on April 12, 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

^ "Polyester rope natural irrigation technique 2". Diyrecipes.com. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

^ "DIY instructions for making self-watering system using ropes". Instructables.c om. 2008-03-17. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

^ Wastewater use in agriculture: Not only an issue where water is scarce! International Water Management Institute, 2010. Water Issue Brief 4

^ http://www.hydrol-earth-syst-sci.net/17/4339/2013/hess-17-4339-2013.pdf

^ "Water use efficiency - agriwaterpedia.info".

^ Chartres, C. and Varma, S. Out of water. From Abundance to Scarcity and How to Solve the World's Water Problems FT Press (USA), 2010

^ "Reengaging in Agricultural Water Management: Challenges and Options". The World Bank. pp.4-5. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

^ Molden, D. (Ed). Water for food, Water for life: A Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture. Earthscan/IWMI, 2007.

^ ILRI, 1989, Effectiveness and Social/Environmental Impacts of Irrigation Projects: a Review. In: Annual Report 1988, International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement (ILRI), Wageningen, The Netherlands, pp. 18 - 34 . On line: [1]

^ Ros egrant, Mark W., and Hans P. Binswanger. "Markets in tradable water rights: potential for efficiency gains in developing country water resource allocation." World development (1994) 22#11 pp: 1613-1625.

^ EOS magazine, september 2009

^ World Water Council

^ Hukkinen, Janne, Emery Roe, and Gene I. Rochlin. "A salt on the land: A narrative analysis of the controversy over irrigation-related salinity and toxicity in California's San Joaquin Valley." Policy Sciences 23.4 (1990): 307-329. online

^ Drainage Manual: A Guide to Integrating Plant, Soil, and Water Relationships for Drainage of Irrigated Lands. Interior Dept., Bureau of Reclamation. 1993. ISBN0-16-061623-9.

^ "Free articles and software on drainage of waterlogged land and soil salinity control in irrigated land". Retrieved 2010-07-28.

^ UV treatment http://www.uvo3.co.uk/?go=Irrigation_Water

^ ultrasonic algae control http://www.lgsonic.com/irrigation-water-treatment/

Fur ther reading

Elvin, Mark. The retreat of the elephants: an environmental history of China (Yale University Press, 2004)

Hallows, Peter J., and Donald G. Thompson. History of irrigation in Australia ANCID, 1995.

Howell, Terry. "Drops of life in the history of irrigation." Irrigation journal 3 (2000): 26-33. the history of sprinker systems online

Hassan, John. A history of water in modern England and Wales (Manchester University Press, 1998)

Vaidyanathan, A. Water resource management: institutions and irrigation development in India (Oxford University Press, 1999)

Journals

Irrigation Science, ISSN1432-1319 (electronic) 0342-7188 (paper), Springer

Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering, ISSN0733-9437, ASCE Publications

Irrigation and Drainage, ISSN1531-0361, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

External links

Look up irrigation in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Irrigation.

"Irrigation techniques". USGS. Retrieved December 8, 2005.

Royal Engineers Museum: 19th century Irrigation in India

[2]< br>

International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage (ICID)

When2Water.com Tutorial and online calculators related to agricultural irrigation

Irrigation at the Water Quality Information Center, U.S. Department of Agriculture

AQUASTAT: FAO's global information system on water and agriculture

Irrigation Supplies: Principles of Water Irrigation Systems

Irrigation & Gardening: Future Of Irrigation Needs

"Lamp Wick Solves Problem of Citrus Irrigation" Popular Mechanics, November 1930

World Bank report on Agricultural water management Irrigation is discussed in chps. 1&4.

v

t

e

Water resources management and irrigation by country

Africa

Burkina Faso

Egypt

Mali

Morocco

South Africa

Sudan

Tanzania

Asia

Afghanistan

Bangladesh

China

Iran

Iraq

India

Israel

Kazakhstan

Pakistan

Saudi Arabia

Syria

Turkey

Turkmenistan

Europe

Belgium

Italy

Russia

North America

Belize

Canada

Costa Rica

Dominican Republic

El Salvador

Guatemala

Honduras

Jamaica

Mexico

Nicaragua

United States

Oceania

Australia

New Zealand

Indonesia

Philippines

South America

Argentina

Bolivia

Brazil - supply

Brazil - irrigation

Chile

Colombia

Peru

Uruguay

List of countries by irrigated land area

v

t

e

Agricultural water management

Irrigation

Surface irrigation

Drip irrigation

Tidal irrigation

Irrigation of alluvial fans

Irrigation statistics

Irrigation management

Irrigation environmental impacts

Subsurface drainage

Tile drainage

Drainage equation

Drainage system (agriculture)

Watertable control

Drainage research

Drainage by wells

Surface water/runoff

Contour trenching

Hydrological modelling

Hydrological transport model

Runoff model (reservoir)

Groundwater

Groundwater flow

Groundwater energy balance

Groundwater model

Hydraulic conductivity

Watertable

Problem soils

Acid sulphate soils

< br>Alkali soils

Saline soils

Agro-hydro-salinity group

Hydrology (agriculture)

Soil salinity control

Leaching model (soil)

SaltMod integrated model

SahysMod polygonal model: Saltmod coupled to a groundwater model

Related topics

Sand dam

v

t

e

Natural resources

Air

Pollution/ quality

Ambient standards (USA)

Index

Indoor

developing nations

Law

Clean Air Act (USA)

Ozone depletion

Emissions

Airshed

Trading

Deforestation (REDD)

Energy

Law

Resources

Fossil fuels(peak oil)

Geothermal

Nuclear

Solar

sunlight

shade

Tidal

Wave

Wind

Land

Arable

peak farmland

Degradation

Law

property

Management

habitat conservation

Minerals

mining

law

sand

peak

rights

Soil

conservation

fertility

health

resilience

Use

planning

reserve

Life

Biodiversity

Bioprospecting

Biosphere

Bushfood

Bushmeat

Fisheries

law

management

Food

Forests

genetic resources

law

management

Game

law

Gene bank

Herbalist plants

Marine conservation

Non-timber forest products

Rangeland

Seed bank

Wildlife

conservation

management

Wood

Water

Types/ location

Aquifer

storage and recovery

Drinking

Fresh

Groundwater

pollution

recharge

remediation

Hydrosphere

Ice

bergs

glacial

polar

Irrigation

Rain

harvesting

Stormwater

Surface water

Wastewater

reclaimed

Aspects

Desalination

Floods

Law

Leaching

Sanitation

Conflict

Conservation

Peak water

Pollution

Privatization

Quality

Right

Resources

management

policy

Related

Common land

common-pool

enclosure

global

tragedy theory

Economics

ecological

Ecosystem services

Exploitation

overexploitation

Management

adaptive

Natural capi tal

accounting

Nature reserve

Systems ecology

Urban ecology

Wilderness

Resource

Conflict (perpetuation)

Curse

Depletion

Extraction

Nationalism

Renewable/ Non-renewable

Agriculture and agronomy

Energy

Environment

Fishing

Forestry

Mining

Water

Wetlands

agencies

law

management

ministries

organizations

Colleges

v

t

e

Wastewater

Sources

Acid mine drainage

Ballast water

Bathroom

Blackwater (coal)

Blackwater ( waste)

Boiler blowdown

Brine

Combined sewer

Cooling tower

Cooling water

Fecal sludge

Greywater

Infiltration/Inflow

Industrial effluent

Ion exchange

Leachate

Manure

Papermaking

Produced water

Return flow

Reverse osmosis

Sanitary sewer

Septage

Sewage

Sewage sludge

Toilet

Urban runoff

Quality indicators

Biochemical oxygen demand

Chemical oxygen demand

Coliform index

Dissolved oxygen

Heavy metals

pH

Salinity

Temperature

Total dissolved solids

Total suspended solids

Turbidity

Treatment options

Activated sludge

Aerated lagoon

Agricultural wastewater treatment

API oil-water separator

Carbon filtration

Chlorination

Clarifier

Constructed wetland

Decentralized wastewater system

Exten ded aeration

Facultative lagoon

Fecal sludge management

Filtration

Imhoff tank

Industrial wastewater treatment

Ion exchange

Membrane bioreactor

Reverse osmosis

Rotating biological contactor

Secondary treatment

Sedimentation

Septic tank

Settling basin

Sewage sludge treatment

Sewage treatment

Stabilization pond

Trickling filter

Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation

UASB

Vermifilter

Wastewater treatment plant

Disposal options

Combined sewer

Evaporation pond

Groundwater recharge

Infiltration basin

Injection well

Irrigation

Marine dumping

Marine outfall

Reclaimed water

Sanitary sewer

Septic drain field

Sewage farm

Storm drain

Surface runoff

v

t

e

Prehistoric technology

Prehistory

timeline

outlin e

Stone Age

subdivisions

New Stone Age

synoptic table

Technology

history

Tools

Farming

Neolithic Revolution

founder crops

New World crops

Ard/ plough

Celt

Digging stick

Domestication

Goad

Irrigation

Secondary products

Sickle

Terracing

Food processing

Fire

Basket

Cooking

Earth oven

Granaries

Grinding slab

Ground stone

Hearth

A??kl? Hyk

Qesem Cave

Manos

Metate

Mortar and pestle

Pottery

Quern-stone

Storage pit

Hunting

Arrow

Boomerang

throwing stick

Bow and arrow

history

Nets

Spear

Spear-thrower

baton

harpoon

woomera

Schningen Spears

Projectile points

Arrowhead

Bare Island

Cascade

Clovis

Cresswell

< br>Cumberland

Eden

Folsom

Lamoka

Manis Site

Plano

Transverse arrowhead

Systems

Game drive system

Buffalo jump

Toolmaking

Earliest toolmaking

Oldowan

Acheulean

Mousterian

Clovis culture

Cupstone

Fire hardening

Gravettian culture

Hafting

Hand axe

Grooves

Langdale axe industry

Levallois technique

Lithic core

Lithic reduction

analysis

debitage

flake

Lithic technology

Magdalenian culture

Metallurgy

Microblade technology

Mining

Prepared-core technique

Solutrean industry

Striking platform

Tool stone

Uniface

Yubetsu technique

Other tools

Adze

Awl

bone

Axe

Bannerstone

Blade

prismatic

Bone tool

Bow drill

Burin

Canoe

Oar

Pesse ca noe

Chopper

tool

Cleaver

Denticulate tool

Fire plough

Fire-saw

Hammerstone

Knife

Microlith

Quern-stone

Racloir

Rope

Scraper

side

Stone tool

Tally stick

Weapons

Wheel

illustration

Architecture

Ceremonial

Gbekli Tepe

Kiva

Standing stones

megalith

row

Stonehenge

Pyramid

Dwellings

Neolithic architecture

British megalith architecture

Nordic megalith architecture

Burdei

Cave

Cliff dwelling

Dugout

Hut

Quiggly hole

Jacal

Longhouse

Mud brick

Mehrgarh

Neolithic long house

Pit-house

Pueblitos

Pueblo

Rock shelter

Blombos Cave

Abri de la Madeleine

Sibudu Cave

Stone roof

Roundhouse

Stilt house

Alp pile dwellings

Wattle and daub

Water management

Check dam

Cistern

Flush toilet

Reservoir

Water well

Other architecture

Archaeological features

Broch

Burnt mound

fulacht fiadh

Causewayed enclosure

Tor enclosure

Circular enclosure

Goseck

Cursus

Henge

Thornborough

Oldest buildings

Megalithic architectural elements

Midden

Timber circle

Timber trackway

Sweet Track

Arts and culture

Material goods

Baskets

Beadwork

Beds

Chalcolithic

Clothing/textiles

timeline

Cosmetics

Glue

Hides

shoes

tzi

Jewelry

amber use

Mirrors

Pottery

Cardium

Grooved ware

Linear

J?mon

Unstan ware

Sewing needle

Weaving

Wine

Winery

wine press

Prehistoric art

Art of the Upper Pa leolithic

Art of the Middle Paleolithic

Blombos Cave

List of Stone Age art

Bird stone

Bradshaw rock paintings

Cairn

Carved Stone Balls

Cave paintings

painting

pigment

Cup and ring mark

Geoglyph

Golden hats

Guardian stones

Megalithic art

Petroform

Petroglyph

Petrosomatoglyph

Pictogram

Rock art

Stone carving

Sculpture

Statue menhir

Stone circle

list

British Isles and Brittany

Venus figurines

Burial

Burial mounds

Bowl barrow

Round barrow

Mound Builders culture

U.S. sites

Chamber tomb

Severn-Cotswold

Cist

Dartmoor kistvaens

Clava cairn

Court tomb

Cremation

Dolmen

Great dolmen

Funeral pyre

Gallery grave

transepted

wedge-shaped

Grave goods

Jar burial

L ong barrow

unchambered

Grnsalen

Megalithic tomb

Mummy

Passage grave

Rectangular dolmen

Ring cairn

Simple dolmen

Stone box grave

Tor cairn

Tumulus

Unchambered long cairn

Other cultural

Astronomy

sites

lunar calendar

Behavioral modernity

Origin of language

Prehistoric medicine

trepanning

Evolutionary musicology

music archaeology

Prehistoric music

Alligator drum

flutes

Divje Babe flute

gudi

Prehistoric numerals

Origin of religion

Paleolithic religion

Prehistoric religion

Spiritual drug use

Prehistoric warfare

Symbols

symbolism

Authority control

LCCN: sh00006268

GND: 4006306-9

NDL: 00568646

Retrieved from "https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Irrigation&oldid=784200454"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irrigation

No comments:

Post a Comment